NICK SCHRIVER LOOKS at highways the way in which a contractor seems at your own home. He sees hassle spots that may use some touch-ups, if not complete reconstructions. The upkeep supervisor for the Montana Division of Transportation’s northeast subject workplace, Schriver is tasked with ensuring roads in his district are intact and as secure as supposed.

His isn’t any workplace job. As an alternative, Schriver drives a thousand miles of two-lane in his MDT pickup no less than as soon as per week, noting broken indicators, crumbling asphalt, plugged culverts, and roadkill. At all times roadkill. His district consists of a number of the gamiest landscapes in North America, swaths of open prairie that pronghorn antelope cross on their thousand-year-old seasonal migrations, riverbottoms stuffed with whitetails, and Hello-Line two-lanes dotted with grazing mule deer.

Schriver takes me on a tour of essentially the most problematic areas in his district, spots the place roadside vegetation grows proper as much as the shoulder, obscuring wildlife. Or stretches the place the terrain funnels migrating antelope into just some hundred yards of blacktop.

“Right here’s one the place I guess we’ve picked up dozens, possibly even lots of, of lifeless deer through the years,” says Schriver, stopping on the slender shoulder on the east facet of Nashua, somewhat city on U.S. Freeway 2 between the prairie oases of Glasgow and Wolf Level. “Mixture of whitetails and muleys, and the occasional antelope in unhealthy winters when the snow pushes them onto the freeway. The one purpose extra deer aren’t killed right here is as a result of the pace restrict remains to be 55” popping out of the town limits.

On one facet of the freeway, Porcupine Creek meanders by groves of shady ash timber. On the opposite facet stands a winter wheat subject. It’s a basic transition zone between cowl and feed, and Schriver says that for motorists who aren’t watchful, it’s a persistent hassle spot for collisions as deer transfer between the habitats. I see glints of security glass and shards of reflector and turn-signal plastic all alongside the shoulder. Simply forward is a white cross on a metallic T-post, signifying the very spot the place a driver died.

Wildlife collisions are routinely reported to the Montana Freeway Patrol, both by an officer who responds to the scene or by a motorist recording the incident for insurance coverage functions. However many extra accidents are by no means documented, says Tom Martin, environmental bureau chief within the Montana Division of Transportation’s Helena headquarters.

“If a trucker hits a deer, that normally doesn’t trigger them to cease,” says Martin. “So there was a collision, however it was by no means reported, however later we discover a carcass. We all know that carcass knowledge is normally larger than collision knowledge. And our carcass knowledge is conservative.”

By “conservative,” Martin implies that roadkill totals are actually larger than reported. The precise carnage, all gristle and paunch, is collected by Schriver’s groups. These are the carrion crews, MDT employees who patrol their districts no less than weekly, peeling up the carcasses of shattered deer and putrid porcupines. Not each carcass makes it onto the flatbed of the pickup after which to a landfill. In distant areas, the crew generally drags stays far off the freeway, leaving them the place scavengers gained’t be more likely to turn out to be roadkill themselves. However it doesn’t matter what they do with the carcass, each time crews encounter roadkill, they be aware the placement, species, and situation. That info can also be despatched to Helena, the place it joins the collision studies in essentially the most grisly database in Montana, maintained by MDT’s Doug McBroom.

“We have now about 30,000 knowledge factors that we’ve entered since we went stay with our digital reporting system in 2017,” says McBroom, who shares his collision location knowledge with the parents who design and construct Montana’s highways. These statistics are a tributary for a river of data more and more getting used to scale back roadkill and to make sure that wildlife can stay the punchline of the simplest of jokes: to get to the opposite facet.

A Hazardous Actuality

Each deer crash is a variation on Leo Tolstoy’s descriptions of human households: much like others in its themes, however sad in its personal particular manner.

Among the many unlucky shared particulars are too-late consciousness of a twitchy deer on the shoulder, screeching tires, a black cloud of profanity, and the devastating crunch and shudder of influence. Then silence, hissing engine liquids, and hushed check-ins. “Are you OK?” “What simply occurred?” “Jesus…”

Depth and injury parallels Bergmann’s Rule, the precept that bigger species are present in northerly latitudes. Colliding with an elk or a moose is proportionately extra catastrophic than hitting a raccoon or a squirrel. However no wildlife collision is comfortable, for both the motorist or the animal. Hitting wildlife with our automobiles prices Individuals greater than $8 billion yearly, and the roadside carnage is astonishing. Yearly we whack, smack, smoke, grease, and paste an estimated 2 million deer, pronghorns, rabbits, and bears with our automobiles. Whereas some limp away, most animals die both on influence or shortly after from damaged bones or inside hemorrhaging. Even graver are the human prices: 26,000 accidents and a few 200 deaths yearly.

There are penalties for survivors. Motorists might be so traumatized by wildlife collisions that they keep away from troublesome stretches of highway, or cease driving altogether. For animals whose habitat is crossed by roads, avoiding demise by bumper and grille is simply a part of the consideration. At a sure site visitors depth, wildlife merely cease attempting to cross, vacating crucial habitats; others should make problematic detours as a way to cross safely.

However there’s a shocking upside to all that carnage. Each deer, antelope, elk, or bear that’s hit on a freeway helps its survivors keep away from the identical destiny. That is the story of the intense facet of roadkill.

Submit and Wire

After we depart the carnage of east Nashua, Nick Schriver takes me to a spot that has stored his carcass-collection crew busy for the previous 30 years. It’s a stretch of Montana Freeway 200 between the dusty city of Jordan and the hopefully-named crossroads of Flowing Wells, the place the one water for miles round is disbursed by the bathrooms and washbasins of an official state freeway relaxation cease.

As we drive west onto SR200 from Flowing Wells, Schriver prepares me for what we’re about to see.

“This was a spot the place so many mule deer had been hit that the locals received bored with slowing down for the stay ones or stopping to pull the lifeless ones off the highway.”

I’ve pushed this stretch lots of of instances and at all times acknowledged it as problematic. It’s a spot the place adobe buttes stoop proper towards the slender roadway, and the place meandering prairie streams come to a tough cease towards the freeway embankment. Each acre in each course is deer habitat, and the two-lane itself appears misplaced, a black line thrown throughout the rippled prairie. However Schriver exhibits me a brand new dimension to the freeway, a wildlife-excluding fence underneath building alongside the freeway for possibly 30 miles west of Flowing Wells.

In a panorama outlined by countless horizons, the 10-foot-high fence appears even taller. This double-high woven-wire fence runs nearer to the highway than the usual 5-foot barbed cattle enclosure, and each mile or so is a curious hole that appears like a loading dock for 18-wheelers. These are “off-ramps” for deer and pronghorn antelope that may discover their manner contained in the fence and be determined to get out, Schriver tells me.

“The fence is designed to maintain critters off the highway, however generally they’ll get in an open finish, and except you might have some solution to get them out, it’s just about a demise lure,” says Schriver. “I’d name these one-way ramps. They’re designed in order that an animal can soar off to get off the freeway, however an animal from outdoors is just not going to have the ability to soar up on one to get onto the highway.”

Schriver may not have constructed this fence, however his work contributed to its erection. All the information that he and his crew despatched to McBroom through the years helped spotlight this as one among a dozen “hassle spots” within the state that scare the shit out of each rural driver. These are the stretches of freeway with restricted visibility and such a relentless presence of deer crossing the freeway—or nervously about to—that you may inform guests from locals as a result of the latter drive slowly by these gauntlets.

The fence is known as a “wildlife lodging,” and you’ll anticipate to see much more of them within the coming years, in Montana and throughout the West. They’re culverts, underpasses, wildlife-friendly overcrossings, or some other infrastructure that lets wildlife cross over or underneath the highway with out getting smoked by a Suburban.

“An lodging could possibly be a security want, for people and for animals, or it could possibly be a connectivity want—animals are having hassle getting from one facet of the highway to the opposite, for no matter purpose,” says the MDT’s Tom Martin. “However security is basically the most important one for us.”

Tunnels and Bridges

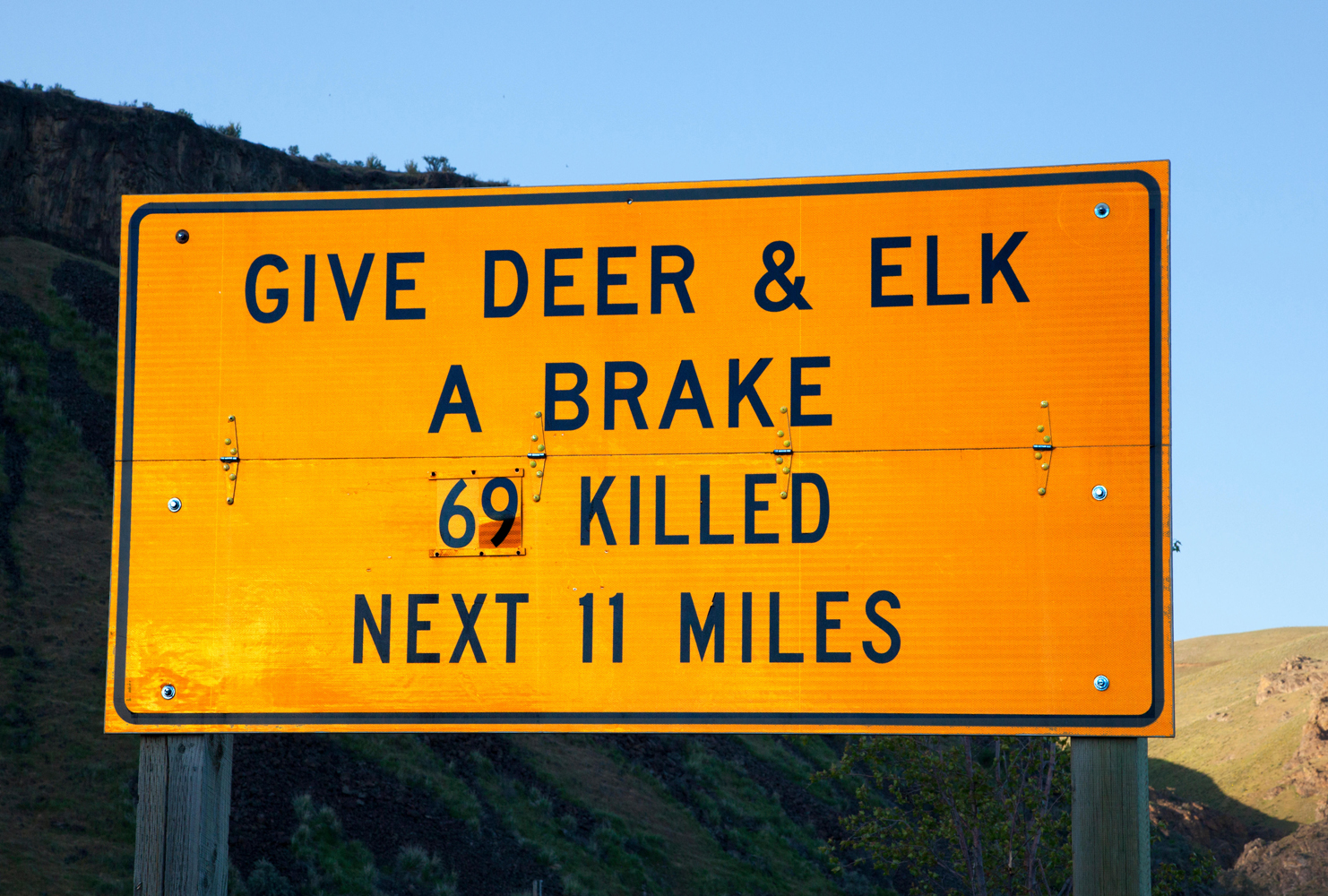

These lodging typically begin with a easy signal. All these yellow indicators that includes a leaping deer or elk or the phrases “Wildlife Crossing” that we routinely ignore had been erected for a purpose: These are spots the place drivers identical to you frequently hit animals.

Subsequent is exclusionary fencing, like what’s on Freeway 200, or the alternative of barbed wire with clean wire because the lowest strand of a regular roadside fence. The graceful wire permits antelope to scoot underneath the fence and cross the highway shortly slightly than milling alongside the shoulder, impeded by the barbed wire.

Within the Southwest, the place endangered desert tortoises are notably inclined to being hit by automobiles as they transfer (slowly) between seasonal habitats, the fence mesh is finer—1×2-inch squares—and the fence itself is decrease—solely 24 inches excessive. However the tortoise fence does the identical factor as a deer fence—it funnels animals to specifically designed culverts the place they will safely cross beneath the freeway.

As a result of they’re least expensive, fences are sometimes the primary possibility thought-about, adopted by culverts. The most costly choices—generally costing tens of tens of millions of {dollars}—are over-crossings, or wildlife-friendly bridges. The prices of constructing and upkeep are at all times taken into consideration earlier than they’re added to a freeway venture, says Martin. That’s as a result of whereas the federal authorities funds cowl three-quarters of most state freeway building and reconstruction tasks, ongoing upkeep is roofed totally by state funds.

“We need to be certain [every accommodation is] affordable and possible and that we’ve got the price range to maintain it long-term,” he says. Which means 30 years for freeway surfaces and 100 years for bridge buildings. “If it meets all these standards, then it will get put into plans and contractors construct it.”

Roadkill by the Numbers

With 8,100 miles of roads maintained by the Division of Transportation alone and plentiful big-game herds in each nook of the state, Montana has a number of alternative for wildlife collisions. Second solely to West Virginia in State Farm Insurance coverage’s nationwide animal-collision likelihood rankings, Montana is nonetheless nicely behind its neighbor Wyoming in addressing roadkill.

The Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Initiative goals to direct some $10 million in federal infrastructure funding to lowering the 6,000 annual wildlife collisions throughout the state. By far, the species almost certainly to die by car within the Cowboy State is the mule deer. The Wyoming Recreation and Fish Division estimates that 4 % of the state’s mule deer inhabitants is killed by automobiles yearly. However that $10 million is only for figuring out the place and what sorts of lodging would possibly cut back the carnage. The worth of establishing them will probably be within the billions, paid primarily by the federal authorities.

That federal pot simply received so much greater. As a part of final December’s federal infrastructure regulation, Congress devoted $350 million over 5 years to the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, which goals to incentivize states, municipalities, tribes, and NGOs to submit plans to scale back wildlife mortality within the spots with the most important roadkill issues. That’s along with the $350 billion the regulation appropriated for freeway tasks over the subsequent 5 years.

From places of work in Bozeman, Montana, the Heart for Massive Panorama Conservation is advising candidates on how finest to safe these wildlife-crossing grants. The nonprofit has developed a best-practices toolkit to present candidates a strong likelihood of scoring a federal grant.

Whereas the $350 million gained’t construct out all of the wildlife lodging wanted, Anna Wearn, the CLLC’s director of governmental affairs, is hopeful that it represents a dedication to creating the nation’s roadways much less lethal and intrusive for wildlife, together with aquatic animals resembling fish and amphibians.

“Along with the $350 million, there are billions [of dollars] accessible for wildlife crossings and habitat connectivity tasks sprinkled by a few dozen federal transportation packages,” says Wearn. “We’re optimistic that if people observe the suggestions in our toolkit and design compelling and scientifically knowledgeable proposals, that they are going to be aggressive for funding underneath these multibillion[-dollar] transportation packages.”

Constructing roads which might be secure for motorists and permeable for migrating wildlife is just not solely within the nationwide curiosity, says Wearn, it’s additionally one of many few bipartisan points in Congress and state legislatures proper now. It’s additionally cost-effective.

“There are so few conservation points the place we’ve got a technical resolution that’s as much as 98 % efficient in fixing an issue,” says Wearn. “And these tasks pay for themselves inside various years, relying on the scale, quantity, and species [of animal] getting hit. The simpler a venture is, the quicker the return on the funding.”

Lowering human harm and demise from wildlife collisions can also be an enormous financial savings not solely in anguish and hospitalization, but in addition in lifetime productiveness. One of many grimmer achievements of the insurance coverage trade is the creation of the Human Life Worth Calculator, which may put a price ticket on you. Designed to evaluate how a lot life insurance coverage is required to completely insure your life towards future earnings, the calculator is used to justify the price of accident-reducing freeway tasks. Even a single life saved can offset tens of millions of {dollars} in building prices.

A few of these infrastructure tasks are staggering in each value and ambition. Development on the biggest wildlife-crossing initiative in historical past began this summer time on U.S. Freeway 101 in California’s Liberty Canyon. The $88 million Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is a vegetated bridge that connects the Santa Monica Mountains and the Sierra Madre Mountains and restores passage for mountain lions, mule deer, and wild canines that was reduce off when the 10-lane Ventura Freeway was inbuilt 1971.

Not all wildlife crossings have their very own names and particular tasks. In Florida, the state legislature authorized the Florida Wildlife Hall Act, which is utilizing incentives to preserve as much as 18 million acres of land from the Georgia border to the Everglades. The bold venture goals to attach 10 million acres already underneath some form of conservation safety as a way to facilitate motion of endangered Florida panthers, native snakes and reptiles, even fish and aquatic crops.

In New England, states are mapping and assessing their hundreds of freeway culverts to find out if they’re impeding the passage of fish, amphibians, and reptiles. In Utah, a cell app permits motorists to report roadkill, and simply this yr Wyoming rolled out a cell app that enables drivers to assert roadkill for meals.

Why all this vitality, innovation, and a spotlight on roadkill? Haven’t we been mowing down deer for so long as we’ve been driving automobiles? Liz Fairbank, a highway ecologist with the CLLC, says a number of components are converging to lift consciousness of—and resolve conflicts between—highways and wildlife.

“First, we’re seeing rising fragmentation and improvement of habitats,” she says. “Visitors quantity is rising and the variety of lanes of site visitors is rising, and we’re seeing extra impediments to wildlife motion by way of roads and different sorts of improvement.”

However she says that we’re getting higher at quantifying the issue. The proliferation of GPS-enabled collars on wildlife has given us new insights into the place wild animals transfer and the way highways impede their passage. State freeway statisticians, like Montana’s Doug McBroom, are additionally reporting roadkill and wildlife collisions extra persistently, giving planners and engineers a greater sense of historic hassle spots.

“Initiatives just like the Wyoming Migration Initiative have proven the general public how wildlife are making these long-distance actions and the way they’re having to navigate an entire matrix of private and non-private lands after which fences, railroads, highways,” says Fairbank. “The problems of habitat fragmentation and migration impediments are lastly coming into the mainstream. Folks weren’t conscious of this even 5 years in the past.”

Fairbank mentioned one other consequence of the confluence of highway design and wildlife science is a reconsideration of whether or not extra roads are needed in any respect.

“Much more tasks are beginning to be considered by what we name the mitigation hierarchy,” says Fairbank. “Step one is avoidance. Do we actually want this highway within the first place? The second step is avoidance. OK, so we want this highway, however let’s work to attenuate its impacts. The third step is mitigation. We have already got the highway, and it’s going by delicate habitat. That’s what we’re speaking about after we speak about these wildlife lodging: We’re mitigating the impacts of a highway that we’ve concluded we want.”

Again in northeast Montana, Nick Shriver says his coronary heart sinks somewhat each time he sees an antelope or a mule deer lifeless on the freeway. His first thought is for the motorist, hoping they weren’t injured and that injury to their automobile wasn’t in depth. However then he thinks concerning the animal.

“They had been simply minding their enterprise. It’s not their fault the highway is there,” he says. Schriver pauses. “Moreover, each deer lifeless on the highway is yet another deer I don’t get to hunt.”

This story initially ran within the Migrations Difficulty of Outside Life. Learn extra OL+ tales.